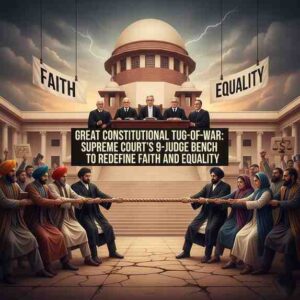

New Delhi, February 2026 — A massive legal shift is underway that could turn India’s professional landscape upside down. The Supreme Court has formed a powerful nine-judge Constitution Bench to answer a question that has simmered for nearly 50 years: Is your local hospital or college actually a factory?

The verdict will decide if millions of professionals—nurses, professors, and NGO workers—should be legally classified as “industrial workers,” a move that would fundamentally change the power balance between employees and management.

The “Triple Test” That Started It All

For decades, the definition of an “industry” has relied on a 1978 ruling known as the Bangalore Water Supply case. In that judgment, the court created a “Triple Test” to identify an industry:

- Systematic Activity: Is the work organized and regular?

- Employer-Employee Relationship: Is there a clear hiring structure?

- Production of Goods or Services: Does the work produce something of value for the community?

This broad definition meant that even non-profit hospitals and universities were treated like factories. While this protected workers, institutions argue it created a “litigation culture” where discipline and service took a backseat to labor disputes.

1947 Laws vs. 2026 Reality

The core of the problem is a “legal mismatch.” India is currently using the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947—a law designed for smoke-belching chimneys and manual factory lines—to regulate a modern economy dominated by corporate hospitals and private “Edu-tech” universities.

The 1947 law simply wasn’t built for a world where the service sector is the primary employer. Critics argue that forcing modern service institutions into a “factory” mold hurts India’s Ease of Doing Business and lowers the quality of essential services like healthcare and education.

What’s at Stake for the Worker?

Classification as an “industrial worker” isn’t just a title—it’s a massive power upgrade. If the court upholds the broad definition, these employees gain:

- The Right to Strike: Legal backing for collective bargaining.

- Union Power: The ability to form unions that can halt operations.

- Labor Court Access: A dedicated legal path to challenge management decisions.

- Retrenchment Protection: Strict legal barriers against being fired or laid off.

The Global Benchmark

India is looking at how developed nations handle this divide. In the UK and the EU, healthcare and education often have their own specific labor standards, recognizing that these “essential services” cannot be managed exactly like a car manufacturing plant. The Supreme Court must now decide if India needs a similar “thin line” between commercial businesses and social services.

Bottom Line

The Supreme Court isn’t just debating definitions; it is deciding the soul of the Indian workplace. Should a hospital be a place of healing or a site of industrial bargaining? Should a college focus on discipline or labor rights?

This judgment will write the next chapter of Indian jurisprudence, balancing the dignity of the worker with the survival of the institution.